Pseudovector

In physics and mathematics, a pseudovector (or axial vector) is a quantity that transforms like a vector under a proper rotation, but gains an additional sign flip under an improper rotation such as a reflection. Geometrically it is the opposite, of equal magnitude but in the opposite direction, of its mirror image. This is as opposed to a true or polar vector (more formally, a contravariant vector), which on reflection matches its mirror image.

In three dimensions the pseudovector p is associated with the cross product of two polar vectors a and b:[2]

The vector p calculated this way is a pseudovector. One example is the normal to a plane. A plane can be defined by two non-parallel vectors, a and b,[3] which can be said to span the plane. The vector a × b is a normal to the plane (there are two normals, one on each side – which can be determined by the right-hand rule), and is a pseudovector. This has consequences in computer graphics where it has to be considered when transforming surface normals.

A number of quantities in physics behave as pseudovectors rather than polar vectors, including magnetic field and angular velocity. In mathematics pseudovectors are equivalent to three dimensional bivectors, from which the transformation rules of pseudovectors can be derived. More generally in n-dimensional geometric algebra pseudovectors are the elements of the algebra with dimension n − 1, written Λn−1Rn. The label 'pseudo' can be further generalized to pseudoscalars and pseudotensors, both of which gain an extra sign flip under improper rotations compared to a true scalar or tensor.

Contents |

Physical examples

Physical examples of pseudovectors include the magnetic field, torque, vorticity, and the angular momentum.

Often, the distinction between vectors and pseudovectors is overlooked, but it becomes important in understanding and exploiting the effect of symmetry on the solution to physical systems. For example, consider the case of an electrical current loop in the z = 0 plane, which has a magnetic field at z = 0 that is oriented in the z direction. This system is symmetric (invariant) under mirror reflections through the plane (an improper rotation), so the magnetic field should be unchanged by the reflection. But reflecting the magnetic field through that plane naively appears to change its sign if it is viewed as a vector field—this contradiction is resolved by realizing that the mirror reflection of the field induces an extra sign flip because of its pseudovector nature, so the mirror flip in the end leaves the magnetic field unchanged as expected.

As another example, consider the pseudovector angular momentum L = r × p. Driving in a car, and looking forward, each of the wheels has an angular momentum vector pointing to the left. If the world is reflected in a mirror which switches the left and right side of the car, the "reflection" of this angular momentum "vector" (viewed as an ordinary vector) points to the right, but the actual angular momentum vector of the wheel still points to the left, corresponding to the extra minus sign in the reflection of a pseudovector. This reflects the fact that the wheels are still turning forward. In comparison, the behaviour of a regular vector, such as the position of the car, is quite different.

To the extent that physical laws would be the same if the universe were reflected in a mirror (equivalently, invariant under parity), the sum of a vector and a pseudovector is not meaningful. However, the weak force, which governs beta decay, does depend on the chirality of the universe, and in this case pseudovectors and vectors are added.

Details

The definition of a "vector" in physics (including both polar vectors and pseudovectors) is more specific than the mathematical definition of "vector" (namely, any element of an abstract vector space). Under the physics definition, a "vector" is required to have components that "transform" in a certain way under a proper rotation: In particular, if everything in the universe were rotated, the vector would rotate in exactly the same way. (The coordinate system is fixed in this discussion; in other words this is the perspective of active transformations.) Mathematically, if everything in the universe undergoes a rotation described by a rotation matrix R, so that a displacement vector x is transformed to x′ = Rx, then any "vector" v must be similarly transformed to v′ = Rv. This important requirement is what distinguishes a vector (which might be composed of, for example, the x, y, and z-components of velocity) from any other triplet of physical quantities (For example, the length, width, and height of a rectangular box cannot be considered the three components of a vector, since rotating the box does not appropriately transform these three components.)

(In the language of differential geometry, this requirement is equivalent to defining a vector to be a tensor of contravariant rank one.)

The discussion so far only relates to proper rotations, i.e. rotations about an axis. However, one can also consider improper rotations, i.e. a mirror-reflection possibly followed by a proper rotation. (One example of an improper rotation is inversion.) Suppose everything in the universe undergoes an improper rotation described by the rotation matrix R, so that a position vector x is transformed to x′ = Rx. If the vector v is a polar vector, it will be transformed to v′ = Rv. If it is a pseudovector, it will be transformed to v′ = -Rv.

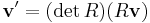

The transformation rules for polar vectors and pseudovectors can be compactly stated as

(polar vector)

(polar vector) (pseudovector)

(pseudovector)

where the symbols are as described above, and the rotation matrix R can be either proper or improper. The symbol det denotes determinant; this formula works because the determinant of proper and improper rotation matrices are +1 and -1, respectively.

Behavior under addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication

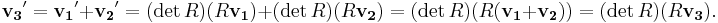

Suppose v1 and v2 are known pseudovectors, and v3 is defined to be their sum, v3=v1+v2. If the universe is transformed by a rotation matrix R, then v3 is transformed to

So v3 is also a pseudovector. Similarly one can show that the difference between two pseudovectors is a pseudovector, that the sum or difference of two polar vectors is a polar vector, that multiplying a polar vector by any real number yields another polar vector, and that multiplying a pseudovector by any real number yields another pseudovector.

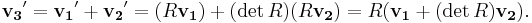

On the other hand, suppose v1 is known to be a polar vector, v2 is known to be a pseudovector, and v3 is defined to be their sum, v3=v1+v2. If the universe is transformed by a rotation matrix R, then v3 is transformed to

Therefore, v3 is neither a polar vector nor a pseudovector. For an improper rotation, v3 does not in general even keep the same magnitude:

but

but  .

.

If the magnitude of v3 were to describe a measurable physical quantity, that would mean that the laws of physics would not appear the same if the universe was viewed in a mirror. In fact, this is exactly what happens in the weak interaction: Certain radioactive decays treat "left" and "right" differently, a phenomenon which can be traced to the summation of a polar vector with a pseudovector in the underlying theory. (See parity violation.)

Behavior under cross products

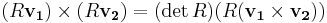

For a rotation matrix R, either proper or improper, the following mathematical equation is always true:

,

,

where v1 and v2 are any three-dimensional vectors. (This equation can be proven either through a geometric argument or through an algebraic calculation, and is well known.)

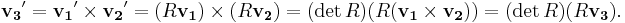

Suppose v1 and v2 are known polar vectors, and v3 is defined to be their cross product, v3=v1×v2. If the universe is transformed by a rotation matrix R, then v3 is transformed to

So v3 is a pseudovector. Similarly, one can show:

- polar vector × polar vector = pseudovector

- pseudovector × pseudovector = pseudovector

- polar vector × pseudovector = polar vector

- pseudovector × polar vector = polar vector

Examples

From the definition, it is clear that a displacement vector is a polar vector. The velocity vector is a displacement vector (a polar vector) divided by time (a scalar), so is also a polar vector. Likewise, the momentum vector is the velocity vector (a polar vector) times mass (a scalar), so is a polar vector. Angular momentum is the cross product of a displacement (a polar vector) and momentum (a polar vector), and is therefore a pseudovector. Continuing this way, it is straightforward to classify any vector as either a pseudovector or polar vector.

The right-hand rule

Above, pseudovectors have been discussed using active transformations. An alternate approach, more along the lines of passive transformations, is to keep the universe fixed, but switch "right-hand rule" with "left-hand rule" and vice-versa everywhere in physics, in particular in the definition of the cross product. Any polar vector (e.g., a translation vector) would be unchanged, but pseudovectors (e.g., the magnetic field vector at a point) would switch signs. Nevertheless, there would be no physical consequences, apart from in the parity-violating phenomena such as certain radioactive decays.[4]

Geometric algebra

In geometric algebra the basic elements are vectors, and these are used to build a hierarchy of elements using the definitions of products in this algebra. In particular, the algebra builds pseudovectors from vectors.

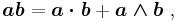

The basic multiplication in the geometric algebra is the geometric product, denoted by simply juxtaposing two vectors as in ab. This product is expressed as:

where the leading term is the customary vector dot product and the second term is called the wedge product. Using the postulates of the algebra, all combinations of dot and wedge products can be evaluated. A terminology to describe the various combinations is provided. For example, a multivector is a summation of k-fold wedge products of various k-values. A k-fold wedge product also is referred to as a k-blade.

In the present context the pseudovector is one of these combinations. This term is attached to a different mulitvector depending upon the dimensions of the space (that is, the number of linearly independent vectors in the space). In three dimensions, the most general 2-blade or bivector can be expressed as a single wedge product and is a pseudovector.[5] In four dimensions, however, the pseudovectors are trivectors.[6] In general, it is a (n - 1)-blade, where n is the dimension of the space and algebra.[7] An n-dimensional space has n vectors and also n pseudovectors. Each pseudovector is formed from the outer (wedge) product of all but one of the n vectors. For instance, in four dimensions where the vectors are: {e1, e2, e3, e4}, the pseudovectors can be written as: {e234, e134, e124, e123}.

Transformations in three dimensions

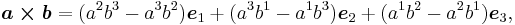

The transformation properties of the pseudovector in three dimensions has been compared to that of the vector cross product by Baylis.[8] He says: "The terms axial vector and pseudovector are often treated as synonymous, but it is quite useful to be able to distinguish a bivector ⋯ from its dual ⋯." To paraphrase Baylis: Given two polar vectors (that is, true vectors) a and b in three dimensions, the cross product composed from a and b is the vector normal to their plane given by c = a × b. Given a set of right-handed orthonormal basis vectors { eℓ }, the cross product is expressed in terms of its components as:

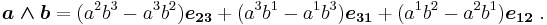

where superscripts label vector components. On the other hand, the plane of the two vectors is represented by the exterior product or wedge product, denoted by a ∧ b. In this context of geometric algebra, this bivector is called a pseudovector, and is the dual of the cross product.[9] The dual of e1 is introduced as e23 ≡ e2e3 = e2 ∧ e3, and so forth. That is, the dual of e1 is the subspace perpendicular to e1, namely the subspace spanned by e2 and e3. With this understanding,[10]

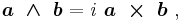

For details see Hodge dual. Comparison shows that the cross product and wedge product are related by:

where i = e1 ∧ e2 ∧ e3 is called the unit pseudoscalar.[11][12] It has the property:[13]

Using the above relations, it is seen that if the vectors a and b are inverted by changing the signs of their components while leaving the basis vectors fixed, both the pseudovector and the cross product are invariant. On the other hand, if the components are fixed and the basis vectors eℓ are inverted, then the pseudovector is invariant, but the cross product changes sign. This behavior of cross products is consistent with their definition as vector-like elements that change sign under transformation from a right-handed to a left-handed coordinate system, unlike polar vectors.

Note on usage

As an aside, it may be noted that not all authors in the field of geometric algebra use the term pseudovector, and some authors follow the terminology that does not distinguish between the pseudovector and the cross product.[14] However, because the cross product does not generalize beyond three dimensions,[15] the notion of pseudovector based upon the cross product also cannot be extended to higher dimensions. The pseudovector as the (n–1)-blade of an n-dimensional space is not so restricted.

Another important note is that pseudovectors, despite their name, are "vectors" in the common mathematical sense, i.e. elements of a vector space. The idea that "a pseudovector is different from a vector" is only true with a different and more specific definition of the term "vector" as discussed above.

Notes

- ^ Stephen A. Fulling, Michael N. Sinyakov, Sergei V. Tischchenko (2000). Linearity and the mathematics of several variables. World Scientific. p. 343. ISBN 9810241968. http://books.google.com/books?id=Eo3mcd_62DsC&pg=RA1-PA343&dq=pseudovector+%22magnetic+field%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=pseudovector%20%22magnetic%20field%22&f=false.

- ^ Aleksandr Ivanovich Borisenko, Ivan Evgenʹevich Tarapov (1979). Vector and tensor analysis with applications (Reprint of 1968 Prentice-Hall ed.). Courier Dover. p. 125. ISBN 0486638332. http://books.google.com/books?id=CRIjIx2ac6AC&pg=PA125&dq=%22C+is+a+pseudovector.+Note+that%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=%22C%20is%20a%20pseudovector.%20Note%20that%22&f=false.

- ^ RP Feynman: §52-5 Polar and axial vectors from Chapter 52: Symmetry and physical laws, in: Feynman Lectures in Physics, Vol. 1

- ^ See Feynman Lectures.

- ^ William M Pezzaglia Jr. (1992). "Clifford algebra derivation of the characteristic hypersurfaces of Maxwell's equations". In Julian Ławrynowicz. Deformations of mathematical structures II. Springer. p. 131 ff. ISBN 0792325761. http://books.google.com/books?id=KfNgBHNUW_cC&pg=PA131.

- ^ In four dimensions, such as a Dirac algebra, the pseudovectors are trivectors. Venzo De Sabbata, Bidyut Kumar Datta (2007). Geometric algebra and applications to physics. CRC Press. p. 64. ISBN 1584887729. http://books.google.com/books?id=AXTQXnws8E8C&pg=PA64&dq=bivector+trivector+pseudovector+%22geometric+algebra%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=bivector%20trivector%20pseudovector%20%22geometric%20algebra%22&f=false.

- ^ . William E Baylis (2004). "§4.2.3 Higher-grade multivectors in Cℓn: Duals". Lectures on Clifford (geometric) algebras and applications. Birkhäuser. p. 100. ISBN 0817632573. http://books.google.com/books?id=oaoLbMS3ErwC&pg=PA100&dq=%22pseudovectors+%28grade+n+-+1+elements%29%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=%22pseudovectors%20%28grade%20n%20-%201%20elements%29%22&f=false.

- ^ William E Baylis (1994). Theoretical methods in the physical sciences: an introduction to problem solving using Maple V. Birkhäuser. p. 234, see footnote. ISBN 081763715X. http://books.google.com/books?id=pEfMq1sxWVEC&pg=PA234.

- ^ R Wareham, J Cameron & J Lasenby (2005). "Application of conformal geometric algebra in computer vision and graphics". Computer algebra and geometric algebra with applications. Springer. p. 330. ISBN 3540262962. http://books.google.com/books?id=uxofVAQE3LoC&pg=PA330&dq=%22is+termed+the+dual+of+x%22&cd=1#v=onepage&q=%22is%20termed%20the%20dual%20of%20x%22&f=false. In three dimensions, a dual may be right-handed or left-handed; see Leo Dorst, Daniel Fontijne, Stephen Mann (2007). "Figure 3.5: Duality of vectors and bivectors in 3-D". Geometric Algebra for Computer Science: An Object-Oriented Approach to Geometry (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann. p. 82. ISBN 0123749425. http://books.google.com/books?id=-1-zRTeCXwgC&pg=PA82.

- ^ Christian Perwass (2009). "§1.5.2 General vectors". Geometric Algebra with Applications in Engineering. Springer. p. 17. ISBN 354089067X. http://books.google.com/books?id=8IOypFqEkPMC&pg=PA17#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ David Hestenes (1999). "The vector cross product". New foundations for classical mechanics: Fundamental Theories of Physics (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 60. ISBN 0792353021. http://books.google.com/books?id=AlvTCEzSI5wC&pg=PA60.

- ^ Venzo De Sabbata, Bidyut Kumar Datta (2007). "The pseudoscalar and imaginary unit". Geometric algebra and applications to physics. CRC Press. p. 53 ff. ISBN 1584887729. http://books.google.com/books?id=AXTQXnws8E8C&pg=PA53.

- ^ Eduardo Bayro Corrochano, Garret Sobczyk (2001). Geometric algebra with applications in science and engineering. Springer. p. 126. ISBN 0817641998. http://books.google.com/books?id=GVqz9-_fiLEC&pg=PA126.

- ^ For example, Bernard Jancewicz (1988). Multivectors and Clifford algebra in electrodynamics. World Scientific. p. 11. ISBN 9971502909. http://books.google.com/books?id=seFyL-UWoj4C&pg=PA11#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Stephen A. Fulling, Michael N. Sinyakov, Sergei V. Tischchenko (2000). Linearity and the mathematics of several variables. World Scientific. p. 340. ISBN 9810241968. http://books.google.com/books?id=Eo3mcd_62DsC&pg=RA1-PA340.

General references

- Richard Feynman, Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. 1 Chap. 52. See §52-5: Polar and axial vectors, p. 52-6

- George B. Arfken and Hans J. Weber, Mathematical Methods for Physicists (Harcourt: San Diego, 2001). (ISBN 0-12-059815-9)

- John David Jackson, Classical Electrodynamics (Wiley: New York, 1999). (ISBN 0-471-30932-X)

- Susan M. Lea, "Mathematics for Physicists" (Thompson: Belmont, 2004) (ISBN 0-534-37997-4)

- Chris Doran and Anthony Lasenby, "Geometric Algebra for Physicists" (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2007) (ISBN 978-0-521-71595-9)

- William E Baylis (2004). "Chapter 4: Applications of Clifford algebras in physics". In Rafał Abłamowicz, Garret Sobczyk. Lectures on Clifford (geometric) algebras and applications. Birkhäuser. p. 100 ff. ISBN 0817632573. http://books.google.com/books?id=oaoLbMS3ErwC&pg=PA100.: The dual of the wedge product a

b is the cross product a × b.

b is the cross product a × b.

See also

- Grassmann algebra

- Clifford algebra

- Orientation (mathematics) - Description of oriented spaces, necessary for pseudovectors

- Orientability - Discussion about non-orientable spaces.